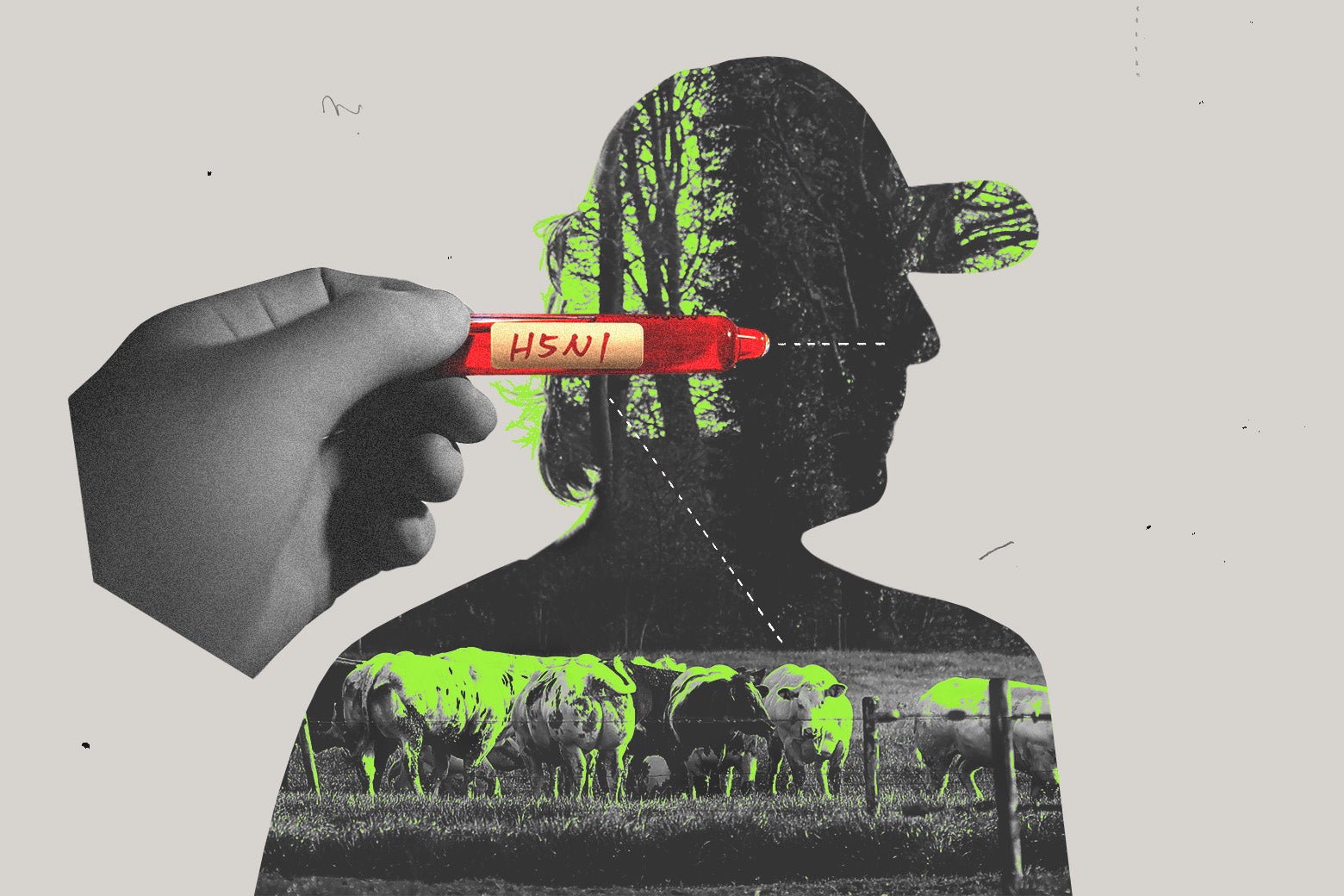

Another Person Was Infected With Bird Flu. What's Going On?

Earlier this month, a farmworker in Texas was infected with bird flu. It’s the second human case detected since the virus’s arrival in the U.S. in late 2021. The illness presented as little more than eye redness, and the patient is on the mend. But the incident stirred up some concern among scientists, in part because of the creature that passed it on: The bird flu was spread to the person not by a bird, but by a cow.

The highly pathogenic influenza virus called H5N1 has been actively ravaging poultry farms around America for a few years, resulting in the culling of more than 82 million farmed birds as of last week. But the Texas infection marked the first time it’s been found on a dairy farm.

Since the discovery, outbreaks among dairy cattle have been reported in seven more states. That number will likely go up as surveillance efforts, which had previously been focused mostly on poultry farms, expand.

There’s a lot that we don’t know, and some things that we do. Let’s talk about it.

I feel like I’ve been hearing about bird flu for a long time.

Yep. The current version of the virus wreaking havoc emerged in 2020, and it made its way to the U.S. about a year later. Another subtype of avian flu made the rounds here back in 2015, but it mostly just affected farmed birds, like chickens and turkeys. This time it’s been decimating wild bird populations too. Pelicans, vultures, and raptors have been especially affected.

So it mostly affects birds, obviously! And now some cows. And a person. Had bird flu been found in other animals, too?

Over the past year or so, the virus has traveled to almost every corner of the world, and to a variety of animals: from polar bears in the Arctic to penguins in Antarctica, and everywhere in between (so far Australia and New Zealand seem to have been spared, says Philip Meade, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine). Some larger outbreaks in particular have been especially worrisome to scientists: a mink farm in Spain (fall 2022); South American sea lions in Peru (spring 2023); and fur farms in Finland (summer 2023).

This level of devastation in wild animals due to avian flu is unprecedented.

If so many species have been infected, why is the cow thing a big deal?

Cows were not previously thought to be susceptible to avian flu, so in and of itself it’s just a surprising development. It’s true that the virus has jumped from bird to mammal several times now. Early evidence suggests that the virus involved in the recent human case had a mutation linked to more efficient spread in mammals. But that mutation has happened several times, including in foxes and cats that have caught H5N1, and it hasn’t resulted in a human outbreak yet.

So, the presence of this mutation alone does not seem to be cause for concern. “Even infection in mammals doesn’t necessarily predict human infection and human transmission,” says epidemiologist Stephen Morse of Columbia University.

OK, but the cow-to-human infection did happen. Yikes?

Yes—kind of. But there are still some open questions. What would be more concerning is if the virus is found to definitely be spreading between cows, as opposed to spreading from bird to cow to human. Cow-to-cow transmission would suggest that the virus has become more adept at transmitting between mammals.

Given the outbreaks on several farms, it seems this possibility is likely, virologist Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital told Nature. But, Meade notes, it’s still very much a developing situation, and we’re learning more every day. The level of concern will depend a lot on the specific mutations the virus has picked up, which scientists are still trying to figure out.

Well, how likely is it to infect humans going forward?

Since H5N1 was first described in 1996, fewer than 1,000 people have been infected; infections have ranged from mild to more severe in other countries besides the U.S. There was one concerning outbreak in Hong Kong back in 1997, when 18 people were affected and six died. And again, so far only two people have been infected in the U.S., ever.

Importantly, those recent infections occurred in people working in close proximity to animals. That suggests that prolonged contact with an infected animal is needed to cause infection in a person. “That’s good news for us because [the virus] doesn’t seem to be particularly good at infecting humans,” Meade says. And, “it means that in our daily lives, birds flying past, stepping on bird poo, that kind of thing—that’s not dangerous.”

But that could change, right?

Yes. And that’s what’s causing concern among scientists. With every new infection, scientists say, there’s another chance for the virus to mutate and become better equipped for infecting humans. “Flu is so unpredictable,” says Morse. “But it’s clear that this virus has been evolving considerably in the last few years, and that it does seem to have much greater ability to infect mammals.”

A very worrying scenario would be if the virus evolves to be able to transmit between people. There is no evidence that this is the case at this time, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

So, how worried should I be?

The CDC human health risk assessment for the U.S. continues to be low.

Since this family of viruses has been circulating worldwide for quite a while, there’s good surveillance for it established in the U.S. and beyond, says geneticist Christine Marizzi, who teaches at Icahn School of Medicine. The World Health Organization, the CDC, and other global health organizations are all in communication, sharing info and genetic sequences with one another. Keeping on top of the latest sequences helps organizations ensure that their stockpiled vaccines and drugs will still be effective for the latest version of the virus if an outbreak among humans does end up occurring.

As far as vaccines go, the CDC has a couple candidate vaccines that could be quickly tweaked and mass produced if needed. There are also at least four antiviral medications that can treat people sick with bird flu, one of which (oseltamivir) is stockpiled by the government to the tune of tens of millions of doses. Generic versions of that drug also exist commercially worldwide.

In general, Meade says: “Be aware but not alarmed.”

OK, I am aware! A couple questions along those lines: consuming milk and eggs … is that OK?

The USDA recently announced there’s no need to worry about this. “Whenever this virus is detected in any agricultural operation, they immediately shut down any movement of products into the market,” says Meade. But even if the virus were in a batch of milk, pasteurization would effectively neutralize it.

Similarly, cooking eggs and meat should be enough for their safe consumption, as long as you’re cooking them thoroughly enough. That being said, officials at the Food and Drug Administration and the United States Department of Agriculture are continuing to monitor the situation in case anything changes.

How do I know if there’s bird flu near me?

You can check out this handy-dandy map to get a sense of where the bird flu is showing up.

While the flu is often discussed in the context of poultry farms or backyards, there’s no reason it won’t show up in urban spaces too. Recently there’s been some media coverage of the confirmation of infected wild birds in New York City. Though this research was only just published, the samples were from back in late 2022 to early 2023. And researchers weren’t surprised by the finding. “It’d be stranger for it not to arrive here,” says Meade of New York City. In fact, if anything, the low prevalence was surprising, Marizzi adds—only six samples tested positive out of over 1,900.

Still, the finding demonstrates that it’s important to be cautious around birds in urban spaces, as well as rural ones.

Ah, there’s bird flu in my area. What do I do?

It’s more what you shouldn’t do: Don’t pick up birds! Don’t kiss them! If you have to pick up an injured bird, wear gloves and a mask! But really—if you see a bird that looks like it needs help, reach out to a local organization rather than handling the matter yourself, and report dead birds to the USDA. Basically: Just follow common sense.